In service management, we come up with solutions and solve problems on a regular basis. It’s part of the job, and we are quite good at it. There are times, however, when a new problem arises and the usual solutions simply don’t work. The problem could be technical, an inefficient work process, a staffing issue, or the need for a strategic approach when standard methods prove ineffective. In those situations, we need to innovate. The challenge is that our normal thought patterns often don’t promote our creative abilities. Instead, they confine us.

To get better solutions, we need to think differently.

Our default thought patterns follow linear or convergent thinking: thoughts converge, step by step, on a linear path toward a single answer. Convergent or linear thinking is great for math problems and any situation where there is only one correct answer. It’s essential in daily activities, since we often experience repeat problems where new solutions aren’t necessary. However, for new or difficult problems, innovation is needed. This requires nonlinear or divergent thinking.

The word divergent is derived from the Latin divergere, meaning "to go in different directions." Divergent thinking provides the freedom to branch out and explore many possible answers or solutions. That might sound easy, but we are inhibited by what Roger von Oech, in A Whack on the Side of the Head, calls "Ten Mental Locks."

-

The Right Answer

-

That’s Not Logical

-

Follow the Rules

-

Be Practical

-

Play Is Frivolous

-

That’s Not My Area

-

Don’t Be Foolish

-

Avoid Ambiguity

-

To Err Is Wrong

-

I’m Not Creative

These locks keep us from tapping our creative potential: "Follow the Rules" confines us to conventional approaches; "Don’t Be Foolish" keeps us from using our imagination; "I’m Not Creative" traps us into believing we can’t come up with better ideas; and "To Err Is Wrong," is rather ironic, as some notable inventions were the result of mistakes: x-rays, penicillin, Post-Its, ink-jet printers, plastic, etc.

The most unfortunate lock on the list is "I’m Not Creative," because it is universally wrong. The average human brain contains approximately 100 billion neurons with the potential to make 100 trillion connections. With that many connections, every one of us has terrific potential for generating ideas. We all have the ability to create innovative solutions, if we just give ourselves permission to think differently.

Many great solutions wouldn’t have been possible using linear thinking alone, because they require creative leaps, not pure logic. For example, on a sunny day in 1944, Edwin Land was on vacation with his family in New Mexico. They were taking pictures of the scenic landscape, and his three-year-old daughter wanted to know when they could see the pictures. At that time, of course, cameras used film that needed to be developed in a lab. Land explained to his daughter that they needed to wait until they got home to have the pictures developed. His daughter, like any child, asked "Why?" She insisted that she should be able to see the pictures right away.

Later that day, Land took a long walk and pondered the problem. He envisioned a scenario where pictures could be developed instantly. He took a creative leap and assumed it was possible. Back at work, he began exploring different approaches. He ultimately invented self-developing film, and the Polaroid Land camera was born. Not knowing the "rules" of photography, Edwin Land’s daughter caused him to alter his thinking, and he revolutionized picture-taking habits around the world.

This example shows how thinking differently can lead to a great invention, but how can the average person create better solutions? First, you need a problem statement. It should be concise and clear so even people unfamiliar with the situation can understand the problem. Second, you need to take a "creative leap." Edward de Bono, considered the "Father of Creative Thinking," posited that the key to getting better solutions is to avoid being constrained by conventional thinking, even if the idea initially seems impossible or strange.

Years ago in Japan, grocery stores couldn’t carry enough watermelons to keep up with demand. The large fruits took up too much space in the size-constrained stores. Then, a farmer on the island of Shikoku had the crazy idea of growing watermelons in a different shape. Through experimentation, he found a way to grow the plants in clear square containers. As the fruit grew, it conformed to the shape of the container. Square watermelons are now very popular in Japan. Stores can carry more fruit, and consumers can fit them more easily in their refrigerators.

As with many inventions and innovations, taking a leap means imagining a solution that may initially seem farfetched. The Wright brothers’ notion that a flying machine was possible is a good example. They were widely ridiculed for their idea because it seemed foolish. You must take that creative leap and project the end state before you can figure out how to take the steps required to achieve it.

One way to cultivate that leap is to frame the problem and brainstorm. Brainstorming involves generating as many ideas as possible without judgment and building on others’ ideas. The wilder the ideas, the better, because even if they aren’t feasible, they open up additional avenues of thought. Most people believe they’ve brainstormed before, but over many years of facilitating such sessions, I’ve found that true brainstorming is rare. People need strong encouragement to let their imaginations loose, and they’re especially inhibited if anyone higher on the management chain is in the room.

During the session I delivered at the HDI 2014 Conference & Expo, I asked how many people had done true brainstorming while their boss was in the room. More than half the room raised their hands. With their hands still in the air, I asked how many of those people had suggested an idea that was illegal or against company policy. Every hand dropped immediately, accompanied by gales of laughter. When I asked why, the response was that those types of ideas would be frowned upon. In other words, they would feel judged, and judgment is the enemy of true brainstorming.

I then explained how typical their experience was, sharing the brainstormed results from another session I had facilitated. The problem statement was: "High school band from Maine wants to participate in the Rose Bowl parade, but has no transportation or funding." The table below lists the brainstormed ideas.

Bake sale |

March there |

Have a car wash |

Bikeathon there |

Get corporate sponsors |

Do a band swap |

Sell cookies |

Steal buses |

Sell uniform ads |

Rob a bank |

Beg for money |

Sell kidneys to raise money |

Sell performances |

Donations via Facebook |

Get celebrity sponsors |

Crowdsource |

Hold a playathon |

Perform via satellite |

Get a grant |

Move the parade to Maine |

On the left are the first ten ideas the group generated. They’re practical, but not very innovative. I paused the session and encouraged them to give me some really crazy ideas, to consciously ignore the Ten Mental Locks. You can see that the ideas on the right are much more innovative—and actually include things that are illegal! No one’s going to actually rob a bank or steal buses, but those crazy ideas could help surface legal ways to get the intended result. Maybe they could borrow buses or get a bank to partner with them on a fundraising effort. With so many different ideas, brainstorming encourages people to combine ideas to create solutions. If I hadn’t encouraged those crazy ideas, their answers would have been safer, but probably not very creative.

Of course, brainstorming doesn’t have to generate crazy ideas to be helpful. Near the end of my session at HDI 2014, we brainstormed solutions to problem statements submitted by the attendees. In response to one problem statement—"staffing gaps due to high turnover in temporary workers"—the group generated more than a dozen potential solutions in less than a minute. The person who submitted the problem stated that several of the ideas she heard were worth exploring. In particular, the suggestion to hire retired service desk staff on a part-time basis to bridge those gaps was most appealing. Although this idea may not seem particularly innovative, it was an idea her company hadn’t considered.

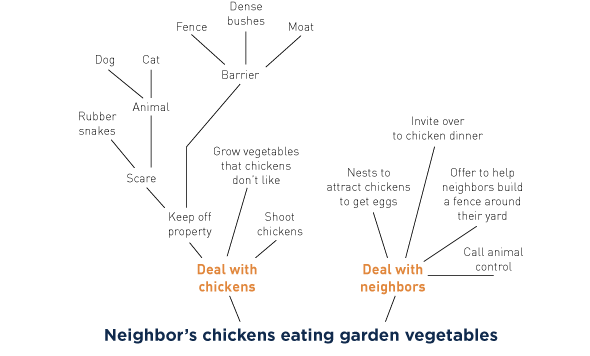

Another technique for generating ideas is called a radial outline. This involves putting the problem statement at the bottom of a page and then creating branches of ideas emanating upward by asking "how" questions. Take, for example, the following problem statement: "The neighbor’s chickens are eating your garden vegetables." The first "how" identifies two general approaches: "deal with chickens" and "deal with neighbors." From there, additional "how" questions spawn more-specific ideas as the branches radiate upward. Each thought acts as a catalyst for others. With additional branches, more innovative ideas can surface. Elaborate radial outlines can have four or five dozen branches, and some of the best ideas can be found at the top.

Brainstorming and radial outlines are two tools that can help generate innovative ideas, but if you search the Internet for "thinking tools," you’ll find an abundance of other tools and techniques. Many of these can be used by individuals or groups. In large-group settings, a skilled facilitator may be needed to get the best results. And, remember, a nonthreatening, judgment-free environment is essential for giving people the freedom for people to branch out in their thinking.

The advancement in technology we see on a continuing basis clearly illustrates that better solutions are out there. They just haven’t been discovered yet. So, when you encounter a situation where the standard approach isn’t getting the results you need, don’t fret. View it as an opportunity. It doesn’t matter if it’s a technical problem, a process issue, or a staffing dilemma. Remember that we all have tremendous capacity to generate great ideas once we give ourselves permission.

Edward de Bono once said, "Creativity involves breaking out of established patterns in order to look at things in a different way." Craft your problem statement and select a tool. Then, branch out, unlock your thinking, and take that creative leap. You’ll be pleasantly surprised with the ideas and solutions you can generate, just by thinking differently.

George Diorio has held leadership positions in the IT industry for more than twenty-five years, with extensive experience in systems engineering, software development, and service management. George is considered to be an expert on professional development, and he has presented on a variety of topics at national conferences. He’s currently the director of IT infrastructure at Martin’s Point Health Care in Portland, ME.