There are many measures that can help your organization understand both the adoption and benefits of knowledge-sharing practices. The five measures presented below represent the ones that I believe are most helpful for all organizations, regardless of size or function. If you're sharing knowledge, these measures will report progress and reinforce behaviors.

But why five? To effectively measure progress and adoption, you need more than one measure, because focusing on one to the exclusion of the others can lead to disaster. A few years ago (I won’t say how many), I was looking for an engagement ring for my then girlfriend. I looked at several different jewelry stores and was impressed by the size of some of the precious stones. It took several stores and a very patient salesperson to educate me in the three C's used to rate diamonds: cut, color, and clarity. These three taken together, along with the size (the fourth C, carat weight) determine the quality and price of the stone. A large stone that has low ratings in color and clarity would not have made a good-quality ring.

The quality of your knowledge-sharing program shares a similar characteristic. If you only focus on one of the areas below, you won’t have a healthy program. You're just trading off success in a single metric for poor performance in another. So use several of these metrics together to gauge your success.

Measure Buy-In for Your Knowledge-Sharing Program

When I first started in knowledge management nearly twenty years ago, we focused on measuring quantity. How many knowledge articles did the team create this past week? How many of them were viewed by someone outside the team? All of us in knowledge sharing learned a great deal from this early approach. Lots of repetitive or low-quality knowledge isn’t useful. Huge repositories where little, if any, knowledge is easy to find are worse than no repositories at all.

If you only focus on one of the areas below, you won’t have a healthy program. You'll simply be trading success in a single metric for poor performance in another.

To truly measure the effectiveness of knowledge sharing in your team, you need to look at several different measures, not just one. The first key metric is staff engagement.

Staff engagement doesn’t have anything to do with how the team does its work. Rather, it has to do with whether the team understands why it's doing the work. Do they understand how finding, reusing, enhancing, and building knowledge benefits them? The people who consume their knowledge? The entire organization? Do they understand how changes to the way they do their work supports access to knowledge when and where it is needed?

If you look at knowledge-sharing practices through the lens of behavioral psychology, then this measure is all about the motivation to share (not the ability or trigger for sharing). It’s a proxy for buy-in. Not perfect, but it’s goes to a sense of how well the organization understands why it's sharing knowledge.

You can improve the organization’s buy-in through consistent communications and well-framed training. (Take a look at the Klever webinar on effective training techniques for some great hints on structuring training. See what experts and other practitioners are saying about communication techniques that have worked in the real world.) In general, you will measure staff engagement through surveys. Frequent touch-points to see whether the team understands the “how.” Below are a few questions/statements to jump-start your survey, using a five-point scale.

- I feel comfortable sharing knowledge with colleagues

- I understand why it's important to share knowledge effectively

- I know how sharing knowledge benefits me

- The leadership team supports sharing knowledge across the organization

- The processes in our organization make knowledge sharing across the organization easy

Measure How Well You Fulfill the Need for Knowledge

The results of a critical knowledge management practices survey by John Ragsdale show that nearly everyone believes knowledge sharing has a major impact on real organizational outcomes. Nearly 75 percent of respondents said that knowledge sharing will deliver at least a 20 percent return on investment. The challenge for most organizations is getting the team to practice knowledge sharing. One of the best ways to motivate an organization is to start measuring the behaviors that you want to change.

To motivate your organization, start by measuring the behaviors you want to change.

Knowledge-sharing practices are complex behaviors, though, so measuring their adoption can be tricky. You have to try, though, because you need an immediate indicator of whether your organization is sharing its knowledge effectively. You can’t wait for the outcome. The second important measure for tracking and implementing knowledge-sharing practices is staff adoption.

Staff adoption is the most important measure of the team’s behavior. How well are individual team members—and the team as a whole—integrating searching, reusing, enhancing, and creating knowledge into what they do every day? From the perspective of a manager or executive, how successful has the organization been in affecting the behavior of the team? Does the team understand why knowledge-sharing practices will make their work better and more fulfilling? Does the tool—wiki, file repository, dedicated knowledge software package—allow the team to access the knowledge they need when and where they need it? Do the changes in team behavior provide the appropriate knowledge when and where a need arises?

What does the measure look like?

Staff adoption is a comparison of two different metric: the number of opportunities the team had to share or reuse knowledge, and the number of times the team actually did. There are two ways to present this measure, depending on your need and audience. If you want to show progress over time (hopefully improvement over time!), you can present staff adoption as a percentage. It tracks well on a line graph if you add a trend line or a running average. If you want to show results, particularly for an executive audience, you can present staff adoption as a ratio. The ratio does a great job of showing how well the team is adopting knowledge-sharing practices at a high level. It stands in for how well your team is leveraging its collective knowledge.

How do you get these two metrics?

In some areas, understanding how well the team is integrating knowledge-sharing practices in their work is simple. In others, it isn’t quite so simple. Why? It’s because different teams encounter different triggers or needs for knowledge, what we at Klever refer to as the four moments of knowledge sharing: need, knowledge discovery/creation, improvement, and habit.

The underlying purpose of knowledge-sharing practices is to match the knowledge to the need for it as quickly and painlessly as possible. For some people, the need is pretty straight-forward. Someone asks us a question, we need knowledge. For others, the need for knowledge isn’t as pressing and immediate. We need knowledge all the time.

There are two key measures for staff adoption:

- Number of cases opened = Number of opportunities to share or reuse knowledge

- Number of cases opened that included a link to a knowledge article = Number of times knowledge was shared or reused

In some teams, the trigger is easy to find and well understood. For support teams—technical support engineers or process support (like HR generalists)—the trigger or need for knowledge is simple and easy to document. A customer or colleague has a question or needs a service. The need is also often documented in a tracking system, like a customer relationship management (CRM) system. CRM systems often can include a link to a knowledge repository as part of the case or request (either a hyperlink or a link within the application, itself).

The underlying purpose of knowledge-sharing practices is to match the knowledge to the need for it as quickly and painlessly as possible.

For other teams, it isn’t as easy to identify when and where knowledge should be shared and reused. Sometimes, you have to use a proxy for reusing knowledge for a team. A project-oriented team might need to rate the knowledge it used (maybe a five-star scale) or provide a place in the project documentation to reference the specific knowledge reuse. For each team, though, we want to know the same thing: How much has the team’s behavior’s changed? Are they searching, reusing, enhancing or creating knowledge?

Measure Knowledge Quality

I come from a long line of gardeners, and I’ve learned a lot from my parents and grandparents. Some of what I learned was very straight-forward. Plants need three basic things to grow: water, nutrients, and sunlight. I also learned that plants need more than the basics to thrive. They need care and tending. That care and tending depends on where I live and what I am planting (in New Orleans, my bougainvillea does best when I ignore it completely).

Knowledge sharing is a lot like gardening. There are fundamental changes we must adopt within our organization so that the knowledge we share doesn’t just do an adequate job, it does a great job. These changes are best measured by looking at staff adoption of knowledge-sharing practices. We also need to measure how well the team is buying into the benefits of sharing their knowledge (our staff engagement measure).

However, there's another area that we need to measure and improve: knowledge quality. Is knowledge easy to find and easy to consume? Is it accurate and up to date? Knowledge quality is more than just a checklist, though: Knowledge quality is a proxy for the perspective of the person who's going to reuse the knowledge.

Up to this point, most of the measures have been about the team. How well are they adopting knowledge sharing practices? Do they get how important knowledge sharing is to the team? Knowledge quality is about the next person who is going to consume the knowledge. Does the formatting make the content easy to consume? Are there spelling or grammar mistakes that detract from understanding the content? Is it easy to determine if the knowledge applies to that person and a specific need?

Knowledge quality is a proxy for the perspective of the person who's going to reuse the knowledge.

The upshot of this focus on the consumer of knowledge is what makes high-quality knowledge vary. It depends on who is consuming it. Sharing a quick procedure with a colleague should be judged on a different set of standards than a report to the board of directors.

There is a three-step process for creating the knowledge quality measure.

- Determine who will consume your knowledge and what they consider to be necessary for quality.

- Are they willing to trade off grammar for faster delivery?

- Are there specific privacy considerations that must be in place for high-quality knowledge (for example, no patient-identifiable information)?

- Create a checklist based on these needs and familiarize the team with the checklist.

- Provide feedback to team members on the knowledge they create.

- Are they hitting the quality checkpoints?

- Are they improving? Some organizations have a formal coaching program around quality; others provide feedback through spot-checks by managers or dedicated knowledge team members.

Here you'll find a sample of a quality spreadsheet for rating knowledge article quality. The quality spreadsheet is one of the ways you help your team improve while making the overall quality of your knowledge repository better. This example is based on a quality spreadsheet from a large, complex support organization. You don't have to use all of these attributes, but this will give you an idea of the range of quality checks you might consider. The sample uses a five-point scale where one is the lowest quality and five is the highest quality.

Measure Time to Competency

This next decade will present unique challenges for businesses as they prepare for the Baby Boomers reaching retirement. One challenge is getting new team members productive as quickly as possible. In western Europe and the United States, waves of retirement in critical industries, like energy, are looming. The costs of onboarding and training new team members to replace these retirees will be substantial, and the transition from retirees to new employees will take an increasingly bigger bite out of productivity, budgets, and margins.

Knowledge sharing is the way forward. By altering the way organizations train their new team members, focusing on how to find what they need to know, not the content itself, training takes less time. (Learn more about new training models in Partnering to Improve Time to Competency, by Emily Dunn and Adam Krob, and on-demand competency from Diane Berry.) Knowledge sharing stops us from trying to download all of the knowledge from our smartest people—which steals productivity from our best team members—and puts all of that knowledge where everyone can find, reuse, and enhance it. That’s why one of the five most important knowledge-sharing measures is time to competency.

Time to competency is a single measure that captures the tangible benefits of knowledge sharing and uncovers whether the behavioral changes are sticking. Time to competency is determined by the number of days it takes a new team member to work independently. You can use the same measure for existing team members acquiring a new skill.

This measure is important for two reasons. First, new team member training time is a significant cost. In one contact center where I worked, we were constantly pushing for shorter training times so we could start billing for new team member time. During that six to eight week training time, we kept more than 100 people on board as pure overhead—a real lost revenue opportunity.

Time to competency is important in another way. It quantifies both the quality and extent of captured team knowledge. If there are significant holes in what team members need to know to do their job, the process of bringing up new team members will expose them. If the quality is poor, trainers and trainees can find and report it quickly. Fortunately, it's relatively easy to measure: How long does it take for a new team member to work independently of the training team? What's surprising is that few companies measure it. Most organizations I have worked with (and for) have a general sense of time to competency, but they've never quantified it. If your organization is in this position, start with your best estimate. Two weeks? Six months? Use the team’s and manager’s impressions as a starting point. With each new team member, measure the time to competency.

Knowledge sharing is the way forward.

As you measure time to competency, measure the effects that knowledge has on it. Start shifting training content to emphasize the knowledge of the entire team. New team members will help identify where knowledge is required and how they would like it to be presented. This feedback will continue to drive down the time to competency, reduce costs, and demonstrate the value of shared knowledge to the entire organization.

Measure Rework Effort

The Talking Heads song "Road to Nowhere" perfectly sums up the problem that knowledge-sharing practices solve: “We know where we’re going, but we don’t know where we’ve been.” Team members confront customer requirements, questions and challenges with their own expertise and experiences, not with what the organization already knows about the customer’s need. The result is hundreds and thousands of hours of effort wasted on rework. Redoing the same project plan. Answering the same question. Fulfilling the same customer need. All while frustrating your customer as they get the same information repeated over and over again.

Knowledge-sharing practices—and the behaviors required to adopt them—could start leading you off this road to nowhere. Every organization that has tried or is trying knowledge sharing is trying to get off this road. But, few organizations know how far they have come and how much farther they need to go. That’s why a measure that quantifies how much your shared knowledge is paying off: rework effort. How much time and effort are you spending on the new and interesting? How much are you spending on the same customer need?

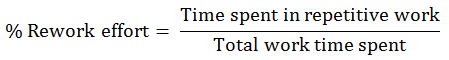

Rework effort is the second measure (time to competency is the first) that shows both the quality and usefulness of the knowledge that the team is sharing and tangible benefits of knowledge sharing. This measure is really a measure of time. Rework effort is the amount of time spent on a repeat customer need. The best way to measure rework effort is by capturing the amount of time spent on all work and categorizing the work as new or rework.

You can gather the data in any way that makes sense for your organization. You might need to create a simple form for your team. You might have a CRM system in place where you can automate gathering the data.

One important note about rework effort: By itself, the percentage of time on rework (or the ratio) isn’t useful. What it can do is provide you context. It can show you where your organization began and how much further you have to go. Seventy percent of time on rework might be fine, particularly if you started at 90 percent.

Rework effort is a critical measure, and there are two important ways to drive change in the measure. First, make sure that the team has integrated knowledge sharing in what they do every day. If they consistently use the knowledge of the entire team, you will gain organizational time and capacity. Second, look at the customer needs/questions/challenges that you spend the most time on. Start adding knowledge to your own repository and share it with your customers (you'll find a template to help you get started here).

Adam Krob, cofounder and CIO of Klever, constantly looks for ways to make knowledge sharing simpler. He came to Klever from The Verghis Group, where he helped companies around the world with their knowledge-sharing programs. Adam received his PhD in political science from Duke University and his MBA from Tulane University.